MANIAGO, Italy

It all started in 1453 when Count Nicolò, the son of Galvano II and Caterina di Strassoldo, obtained from the Lieutenant of Venice the approval to divert the water from the Colvera stream into a "rojale".

This authorization was indispensable, because about thirty years before, the army sent by the Serenissima to bring the peace of Venice into the Friuli homeland, forced the defenders of the castle on the hill of San Giacomo to surrender after a brief siege. This stronghold had near before been taken, and the local nobility were forced to submit to the Doge Mocenigo to conserve their local property.

The intentions of the Count were not only to gain the benefits of carrying water down past Basaldella to irrigate the fields in the plains. He knew that by properly adjusting the height levels of the canals by inserting a number of rises, it would be possible to turn the wheels of the mills and sawmills that were being built along the path of the irrigation channel. The energy of the water was to drive the grinding wheels to grind the gathered materials and the saws to work wood, cut on the slopes of the hills above Maniago, and also to drive the hammers of some small fulling mills to work wool cloth. It must not be forgotten that at that time the economy of the town was mainly rural The construction of the irrigation channel was obstructed by the residents. At night they would fill up the ditch dug by the Count's men during the day, because it prevented carts from moving out into the countryside. So the authorities of Venice had to get involved, requiring Nicolò to build some small bridges.

The importance of that channel was immediately clear to those craftsmen in Maniago who produced farm tools and lumber equipment. If the water could drive mills and saws it would also have to allow the use of the drop hammer for forging steel, which up until then had required the use of heavy sledgehammers.

Along the irrigation channel, the first smith shops (batafiérs) were built, which produced prongs for ploughs, hatchets, scythes, hoes and axes and a number of other useful objects for everyday life (shovels, pickaxes, sheep shears, etc.)

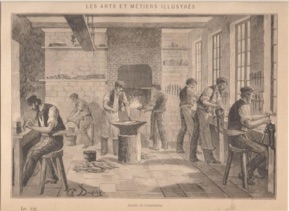

During some periods of military operations, Venice had the local smiths produce weapons, such as during the war against the League of Cambrai). In the smith's shop, the objects had to be obtained by pounding starting with a metal block of a small size, heated red-hot in a furnace. Final shaping was given by the mail operator, whereas the strokes of the "stabilidour" completed the job. For both of these jobs, especially the first, considerable ability and experience was required.

Except for the profile, which had to be sharpened using a grinding wheel, all the rest was left unfinished and rough (which gave rise to the term "fâvri da gros" given to the men of the smithy). This method of working continued through the 1500's and 1600's, but by the 1700's (the century of candles) the request changed. In fact, for goods for everyday use, the appearance of the product became important, not just its function. They also needed a good finish.

Maniago's response was the appearance of the "fâvri da fin", who first set up shop in a corner of the spacious Friulan kitchens and then in a small room attached to the house.

But without the energy of water, this worker could only rely on his own force. Therefore, the objects to me made had to be small, even if, on the contrary of those of the smithies, they could by made up of several components. However, no longer being dependent on the water allowed these small workshops throughout the town.

In the shops of the "fâvris da fin", sharpeners were produced. Typical of Maniago were the filíscjnis and the marineris with the handles respectively in mother-of -pearl and alpaca and cherry wood. There were also scissors and various forms of daggers. The first phase in working was still forging, but now only with the hammer. Finishing was obtained with a pedal-driven grinding wheel and a file. Finally, at the work bench, came assembly and handle insertion.

The work of the smiths, obstructed for much of the 1800's by the government of Vienna who felt it easier to control a farming area rather than and industrial one that was more socialized, picked up again after Italy annexed Veneto (which Friuli was then part of) and after the victory in the third war of independence. The travellers of the Valcellina, who carried in the products out of Maniago in their panniers, were replaced by commerce representatives (known locally as "voyagers"), with their suitcases full of samples and , upon their return, with drawings of tools used in other regions of Italy.

Societa Cooperativa

In the late 1800s a group of iron workers and craftsmen formed Societa Cooperativa Premiata Industria Fabbrile di Maniago. This Cooperative lasted until 1907 and the organization was reformed under a new owner Albert Marx, renamed Marx & C., Coltellerie Riunite.

Marx & C., Coltellerie Riunite

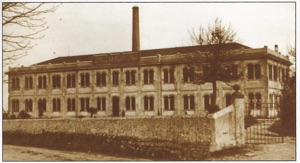

At the beginning of this century the German industrialist Albert Marx built the first workshop, known to the people of Maniago as the "plant" and later as CORICAMA). Some tooling machines were installed in it which allowed mass production. Their movement was made possible through the use of a new form of energy, electricity. The water of the Colvera was still used to drive a small turbine.

Coltellerie Riunite

After WW1, once again the company was reformed and was now simply known as “Coltellerie Riunite” (in English “United Cutlery”).

Making the factory of Marx as an example, several knife factories funded by Italian capital were set up in Maniago after the first world war.

To understand why the name "knife factory" was given to them, it should be remembered that mainly cutting tools were manufactured in Maniago. Therefore, the word "knife" was considered the most suitable symbol to represent this kind of local production.

In these worksites, the technology underwent profound changes with respect to the smithies and workshops. Free forging, with the piece moved under the blows of the mail or the hammer of the operator, was replaced by hot or cold pressing depending on the thickness of the pieces to be worked. With the dies attached to the vertical-drop mails and presses (known in Maniago as cutters), it was possible in one stroke to obtain a from that was very close to the final one.

Co.Ri.Ca.Ma. & Latama Cutlery (U.S.A.)

Following WW2, the Coricama factory pieced up the pieces and stared life again. In late 1947 the American company from Broadway, New York City, Latama Cutlery Inc, connected with Maniago and by 1948 was purchasing switchblade knives from many different Maniago companies before working with Pasquale Patrizio Fabbrica Coltellerie breathing new life into Maniago and the post WW2 boom. Unfortunately switchblades were doomed in NYC by 1952.

In July 1952, the switchblade era between Pasquale Patrizio and Latama came to an end when Latama (and Ethan Products Inc,) signed an exclusive contract with Coricama. By March 1954 switchblades were outlawed in NYC altogether.

Afterwards, with the grinding wheels and passing on to the phase of smoothing, burnishing and polishing, possible with the modification of the type of abrasives that their surface was covered with, a high degree of finish was obtained. The use of another type of energy (heat) made it possible not only to obtain plastic deformation of the steel, but also to ensure the treatments of tempering and hardening, to make the material harder and not as fragile. Although these procedures were used in the previous centuries, what was new was the possibility to protect the steel against corrosion by using nickel or chrome plating or by making use of stainless steels. In the knife factories, a wide range of pocket knives was produced (of various size and shape, multi-use, spring-loaded), for the kitchen, butcher's and scissors for sewing, nails, for barbers and seamstresses, as well as shears for hedges and vines, but also tools for bricklayers (trowels and spatulas) and for surgery (scalpels, forceps, dentists' pliers).

The substantial technological innovations of recent years (such as electrical discharge machining, cutting with water blade, special welding processes, control of high temperatures in furnaces, the availability on the market of abrasives with very fine grain and elevated hardness, the use of numerical control machines) have made it possible not only to increase production in both types and amounts produced, and also to move towards the production of non-traditional items.

The Modern era

Currently in Maniago, gears for complex drive transmissions and blades for steam and gas turbines are produced. In the past these items would have had to have been produced on site. This last consideration brings us to the need to introduce the second parameter referred to at the beginning, which is the great love for their work and the commitment of the smiths of Maniago.

While the products of the workshops is appreciated everywhere and steel working will still have a future, all of this is due to the contribution over five centuries of many modest yet skilled workers in the smithies, workshops and knife factories.

This contribution, the result of appreciable ingenuity but also a spirit of sacrifice, and the knowledgeable and rational use of available energy, have ensured for the local population more well-being that elsewhere, but especially it has made the name of Maniago common with the equally prestigious names of Solingen, Sheffield and Toledo.

-Knife centers in Italy

- Knife museums in Italy

Maniago:

Co.Ri.Ca.Ma. factory

Scarperia:

“Il Museo dei Ferri Taglient di

-Knife companies in Italy

Maniago

Since 1933

Now known as

Alexander & Bufalo

Fine manufactured

materials

Since 1960 featuring the “Jaguar” brand

Since the 1960s

Now known as Due Buoi

Italian stilettos & hunters

Milano

Italy’s premiere cutlery firm since 1946

-Vintage Films

This 1949 Italian b&w 16mm film, “The Portrait of a Town” is a rare glimpse & visual record of the lives of Maniago switchblade Craftsmen

in the late 1940s. It’s incredibly rare that something like this was done in the first place, let alone survives today.

This 1950 Italian b&w 16mm film, features the workshops of Scarperia.

-Extra lnks

A new book made in 2014 by the Cutlery Museum in Scarperia, Italy. Features knives from the collection of Lucio Di Bon including two knives made in the 1890s by “S. Coop.”

and a Latama Square button.

Favorite links:

Maniago circa 1905

Maniago